It was a clear, crisp, October afternoon. Cirrus clouds floated high in the cobalt-blue sky. It was a perfect day to interview the artist Edourdo Benzine and photograph his latest creations before they were thrown into the dumpster. Benzine’s entire oeuvre was a literal take on Yoko Ono’s credo to “destroy the originals,” and today was the day. Benzine admired Yoko’s revolutionary concept of “egoless art” and ran with it. My assignment was to immortalize his totems of creativity in celluloid before they were hauled away to the landfill.

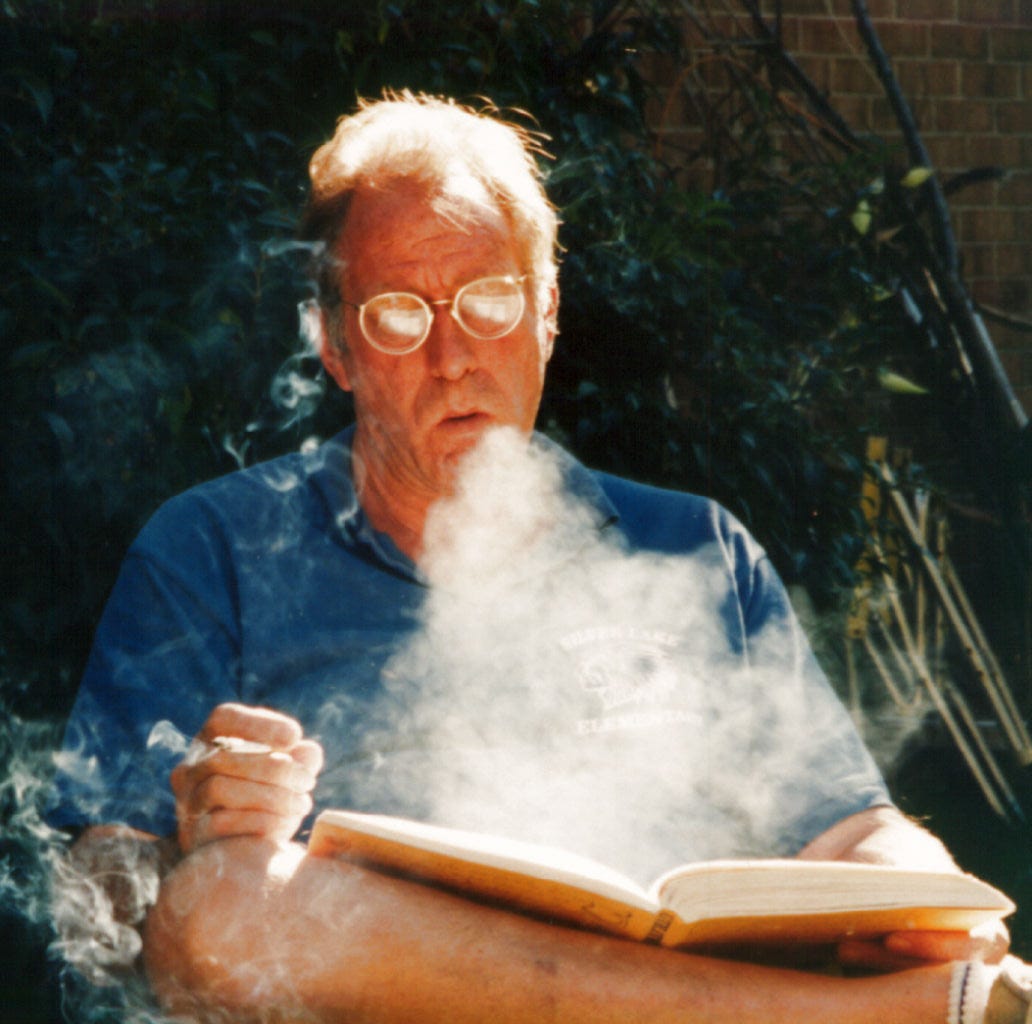

When I arrived at the Villa Belle Arté, the maestro’s ramshackle studio in the suburbs of Newark, Delaware, he was sitting in the yard drinking beer, chain smoking and flipping through an old battered edition of Juggs magazine. 1 As I walked through the gate and announced my arrival he tossed the magazine on the ground, rolled a cigarette and took a deep drag. “Good old Juggs,” he said. “Drives the feminists crazy. I can hear them now. ‘The audacity of those disgusting men, commodifying women as sex objects!’ When I told him some of my feminist friends would consider him a total dick for saying that, he winced. “Well, they missed the point, didn’t they?” he replied. “Juggs was a humor mag, for chrize sakes. Fuck the feminists, if they’ll even let you! Meanwhile, there’s nothing like a nice set of juggs to stimulate the old libido, eh? These wokesters are like the assholes who provoked Lenny Bruce’s satirical retort to the schmucks who deemed “tits and ass” too vulgar to put on the marquee. Lenny’s response was to post the offending words in latin. “Take away the right to say ‘fuck,’” Bruce also said, “and you take away the right to say ‘fuck the government'.” Bob Dylan summed up the whole imbroglio when he said that Bruce “showed the wise men of his day to be nothing more than fools.”

I sat upwind from Benzine to avoid the secondhand smoke and we changed the subject, settling into a discussion about the amazing run-up in prices for art at auction in recent years. “Shocking! Disgusting! Billions of dollars wasted by the One Percenters for crap,” Benzine said. “Most of what you see in the art fair circuit is relatively cheap, and some of it is good, but the price of the stuff auctioned off at the top of the heap is insane. Stars like Jeff Koons and Damien Hirst, for instance, get millions for work of very dubious value. Koon’s famous “Rabbit” sculpture that sold at auction in 2019 for $91 million is a great example. And don’t forget the “Salvator Mundi,” the most expensive painting in the world, which sold at Christie’s in 2017 for $450 million. Meanwhile, most working artists I know sell their stuff for peanuts, if they’re able to sell it at all. In my opinion Andy Warhol nailed the insanity of the art market in his book, The Philosophy of Andy Warhol: “Say you were going to buy a $200,000 painting,” Warhol wrote. “I think you should take that money, tie it up, and hang it on the wall. Then when someone visited you the first thing they would see is the money on the wall.” 2

Warholed! Rare photographic aluminum print by Stewart Whisenant from a collage by Edourdo Benzine, 1987. (available from the author, framed and ready to hang for $200,000, plus postage)

To categorize Benzine as an “outsider artist” or a “dirty, sex-obsessed Bohemian throwback,” as one big-breasted feminist once called him, is to miss his raw, nihilistic essence. “Look, everything ends up in the dumpster eventually,” he said, “that expensive Audi you’re driving, that pricy Tag Huer on your wrist, all that fine art you collect, even all the precious art I create. Every fucking thing under the sun, Jack! It’s all subject to the Law of Thermodynamics in the end. The truth is, you can’t have nothin’. Apparently, not even a planet to put all this shit on if global warming continues unabated. If we’re not careful, a chilly, bitter end of our little blue home of rocks, dirt and water whirling through space will be the human species’ tragic legacy to the universe. The way things are heating up, all that expensive art hanging on the plutocrats’ walls will be worthless. All the credible science says we’ve got about 20 years or so at best, unless we dismantle the global capitalistic juggernaut and stop burning fossil fuels, which doesn't look like it’s gonna happen. That’s why all my art is designed right from the get-go to bypass the the gallery/museum market complex and go directly into the dumpster.”

When Benzine finished talking I asked him about the journal he held cradled on his lap, a big, beat-up leather-bound tome he had been writing in when I arrived. “It’s my manifesto,” he said, “my sacred space for documenting the vagaries of our troubled world.” I then asked him if he would read a few selections aloud and he agreed, taking a deep drag on his cigarette before exhaling long passages of mellifluous prose through a toxic fog of tar and nicotine.

“When I was a child, I felt safe hiding behind the coal bin, while on the floor above me in his oak-paneled library filled with leather-bound first editions, my father paced the parquet floor, brandy snifter in one hand, a Walther .38 caliber in the other hand, swearing oaths in his Harvard educated way and firing random shots toward the thick leather sofa that sprawled beneath the glittering Stuben chandelier, behind which cowered my clueless, Swiss-finished mother. As for me, crouching in the basement, I felt safe in the dirty, dark corner amidst the coal. As the night wore on and the fire burned low in the hearth with the wonderful Thomas Eakins painting above it, a gift from father’s colleagues at the mental institution, the drunken oaths in the room above me turned to raging threats and I relished my haven in the coal bin even more. If this was what life was like behind the massive gates of the villa, up the long, winding drive, past the immense garden filled with exploding colors and funereal odors, then I preferred the safety of the cellar darkness, huddled in the corner, pressed hard up against the anthracite. When the shouting and the shooting ceased and the brandy had its way, I would creep upstairs into the kitchen like a mouse and nibble on the petit-fours and plates of fattening food that were always left uneaten after the opulent dinner parties my parents hosted for their friends. ‘What kind of life was this?’ I wondered and thought I heard amidst the aftermath of chaos and curses in a moment pregnant with unearthly silence, someone call my name: ‘Edourdo! Edourdo! Edourdo Benzine!’”

Edourdo Benzine grew up in a prominent family that was a model of bourgeois gentility. His father was the chief psychiatrist at a local mental hospital who supported his wife and brood of four children in upper-middle class circumstances. Edourdo and his siblings went to private schools and all except Edourdo, finished college and had prosperous careers. Edourdo, the brightest of the bunch, was thrown out of college in his freshman year for riding his motorcycle through the dormitory in the nude. He was drunk at the time, a favored state of being that presaged a difficult future of addiction to alcohol and drugs. Indeed, he was drunk as we talked and continued to get drunker as he read from his manifesto, chain-smoking marijuana-laced, roll-your-own cigarettes and sucking on can after can of the cheap, high-octane beer he’d become addicted to over the years.

“I’ve had to learn to lean on the sustaining infinite,” he read on, “not a paternalistic corporation, or the Catholic Church or a trust fund from daddy. I’ve got nothing to rely on except God himself. But over the years my poverty has humbled me and taught me to trust in the Cosmos and let myself be guided by its wisdom and energy. It’s simple really. This approach doesn’t work very well for rich people, I’ve noticed, only poor folks like myself seem to benefit from this program. It might sound odd, but I’m grateful for my poverty because it simplifies and spiritualizes my life. In my reduced circumstances I can’t do much else except contemplate the cosmos and channel my God-given energy into art. That’s all my art is really—the spontaneous expression of cosmic energy. It’s not planned or thought out in any way. It just happens. That’s when I get the good stuff, the art with soul, which is always the best. How could it be otherwise? As Saint Paul said, “All things work together for good for those who love the Lord and are called to his purpose.”

With these revelations, it was apparent that Benzine’s manifesto served as an inner zoom lens so to speak, capable of changing focal lengths and thus making the artist more visible by portraying him in all the various formative contexts of his life. As he continued to read from his manifesto, Benzine’s words provided a sharp focus on the ephemeral circumstances of his marginal existence at the villa where he had lived for twenty years supported by his maiden aunt, who had suffered a debilitating stroke just a week prior to my visit which necessitated her removal to a nursing home.

“Since I was given the power by God to tell the tale,” Benzine continued, “I will tell it, sort of like Jack Kerouac I suppose, writing at top speed, swerving recklessly from curb to curb, knocking off the hubcaps. Holding a pen while my mind races is like grasping the nozzle of a high-pressure hose out of which information flows and gives my life meaning. We all exist based largely on information—and perhaps a little refined white sugar. What’s Gregory Bateson’s famous definition of information? “A difference that makes a difference!” Yeah, I believe that’s it, but eventually, the image-heavy world of sensory culture drags us down and our vision becomes blurry and coarse. We can no longer see clearly; what was once a starry, starry night is turned into a commodity. The oppressive propaganda of capitalist consumption blocks the flow of inspiration and we can no longer hear Vincent speak to us when we close our eyes. Can you still imagine Vincent’s heart and feel his starry night in yours? Vincent speaks to all who know his name and care enough to listen. But who wants to listen to Vincent in this land of Philistines?”

Although I was struck by Benzine’s flare for words, I was also perplexed by the incongruity between the flamboyant tone of the writing and the derelict demeanor of the author. I then recalled that Vincent Van Gogh had also lived in reduced circumstances, albeit probably not in quite the same dysfunctional squalor that Benzine told me his mother once characterized as “dire and ridiculous.” I also sensed a kinship between Benzine and Henry Darger, a reclusive Chicago artist who died in 1973 and whose bizarre work was critically acclaimed after it was exhibited at the Museum of Folk Art in New York. From all accounts, Darger was something of a nut case who wrote strange stories and painted equally strange watercolors of little girls with penises. After Darger died, his landlord found the artist’s work while cleaning out his tenant’s seedy quarters and recognized his genius. I wondered if the word “genius” applied to Benzine as well. Did his experimental forms transcend the postmodern vision and open up new territory, or was he just a clown and a charlatan? It’s hard to say, because Benzine’s art is not designed to stand alone on its own merits like a traditional painting or sculpture. To fully appreciate his work, Benzine believes the viewer also needs to experience the energy field of the artist himself.

“I want the customer to have direct access to the genius who created the l’object d’art they appreciated enough to give up their hard-earned money for,” he explained. “My aim as an artist is to create a synthesis of artistic entertainment beyond the actual work itself, a process that involves an exchange of values and opinions as well as visual reactions.”

Benzine readily admits that he has no use for art as defined by the American Heritage Dictionary as an activity that reflects “high quality of conception or execution, as found in works of beauty.” Therein lies the rub. The art at Benzine’s Villa Belle Arté isn’t even remotely beautiful. Indeed, in conception and execution it is rather deranged and ugly—in other words, like a lot of the art cluttering the museums and galleries of the world today. In Benzine’s case, his menagerie of useless objects comprise a realm in which things have lost their customary meaning and lurch out of normal context, suggesting that reality is only an arbitrary construction of the mind. Chaotic, irrational, incompatible objects collide in Benzine’s milieu, fulfilling in my estimation, the Surrealist ideal of beauty described in an obscure poem called Songs of Maldoror that contained the phrase: “Beautiful as the encounter of a sewing machine and an umbrella on an operating table.”

To be continued . . .

Dian Hanson, editor, 1986-2001. Juggs Magazine. M M Publications, Ltd. “The magazine of choice for breast men.” - Jerry Saltz/ “The epitome of bad taste.” - Dian Hanson

Andy Warhol, The Philosophy of Andy Warhol, A Harvest Book, Harcourt, INC. 1975.